There’s a big difference between shipping fast and shipping smart. Most of us learn that the hard way—through years of trial, error, and the mentors patient enough to show us a better way.

To help shorten that learning curve, we asked five experienced product leaders and practitioners what they wish everybody knew about product thinking. What we found were honest, practical and refreshingly grounded opinions.

And because we believe clarity comes from sketching ideas early and often, you’ll see how low-fidelity thinking supports each valuable lesson.

Ready to learn? Let’s get into it.

Lesson 1: Know the right questions to ask and when to ask them

A lot of PMs jump straight into solutions. Your CEO asks for a feature because they got excited by a LinkedIn post, and the instinct is to start planning how to build it right away. We get it. But, great product thinking starts by tapping into your own curiosity long before going into solution mode.

Great PMs are skilled interviewers. They know how to get insights even when the problem feels ambiguous. They ask questions that reveal motivations, constraints, and hidden needs. They do this with customers, subject-matter experts, engineers, and leadership. Product Managers are always trying to understand the world around the product before shaping the product itself.

"The best PMs I’ve worked with understand that their job is to create clarity from ambiguity, not to be the smartest person in the room. They spend more time listening to customers, collaborating with their teams, and testing hypotheses than they do writing PRDs or building perfect roadmaps."

By staying curious, you can uncover what’s actually necessary before your team spends a single second on design or code.

A customer interview framework for PMs

To really learn from a customer, start with them—not your product. If you start a conversation by asking about buttons and menus because it’s the world you live in, you’ve already narrowed the conversation too much. You’re leading them to the answers you want rather than uncovering critical information.

"I’ll typically start customer interviews by asking about their day-to-day and who they collaborate with most. Once I understand their context and the conversation starts to flow, I’ll say something like ‘I’d love to hear more about that’ or ‘tell me more about that’ because those tangents often uncover insights that might never surface from scripted questions alone."

You need to understand their needs and business first. Once you understand that, then you can start to figure out how your product fits into it. The best interviews feel like a natural conversation. Use this simple three-step flow to help you get the wheels turning on the right questions to ask:

1. Start by understanding your customers’ context

Before talking about software, find out what their life is like. This helps you see the constraints they’re working under. You can uncover this by asking things like:

- What’s your role in the organization?

- What are the main challenges you’re trying to solve right now?

- What does your typical day-to-day look like?

- Who else is involved in your work? Who do you collaborate with most often?

- What does success look like in your role? How is your performance measured?

- What’s changed in your organization or industry over the past year that’s affected how you work?

2. Bring your product into the conversation organically

Once you have the big picture, you can see where your product fits in. This helps you spot intended usage versus how they’re actually getting work done. You can do this naturally by asking:

- What challenges are you hoping our product can help with?

- Can you walk me through the last time you used our product?

- In your own words, how are you using our product today?

- Are there features you expected to use but haven’t, or vice versa?

- Have you found any workarounds or creative uses we didn’t anticipate?

3. Understand why they chose you (or didn’t)

Finally, try to understand the “why” behind the purchase. Your customer is more likely to reveal what they actually value most about your work if you ask them directly:

- Were you part of the decision to buy this?

- If you were describing our product to a colleague, what would you tell them?

- Have your priorities changed since you first chose our product?

- What other solutions did you seriously consider?

By the end of a chat like this, you’ll be able to validate your ideas faster.

Lesson 2: It’s OK to say no sometimes

Saying yes feels helpful. It feels collaborative. It feels like momentum. But saying yes to everything spreads teams thin, creates technical debt, and confuses users. It also leads to rework, which slows everyone down. Strong PMs understand that prioritization is an act of protection. You protect the product, the team, and the customer experience by choosing what not to do.

"I wish every new PM knew that you shouldn’t fear your customer but be a partner with them. Talk with them frequently and get deep into the context of what they do and why. Also get good at saying ‘no’ because great products are built with amazing prioritization."

Saying no doesn’t close a door forever. It creates space for the right work at the right time. By staying focused on what matters most today, you protect the quality of the product for tomorrow.

Every decision has a cost associated with it

Every feature you build has a price. Engineering time. Maintenance. Opportunity cost. Cognitive load for users. A great PM learns to weigh these costs against the value they create.

"Working closely with engineering taught me that every idea has a cost, so the real work is questioning your assumptions, zooming out, and making evidence-based tradeoffs about what actually moves the product forward."

When you understand these hidden costs, you can stop treating every idea as “free” and start treating your roadmap like the valuable, limited resource it really is.

Lesson 3: Think before you act

Once you understand the problem, it’s tempting to jump straight into building. But speed without direction creates more work later. Great PMs pause before they act. They take a big step back, check their assumptions, and make sure the team is aligned on the “why” behind the work.

"Great product thinking means zooming out before zooming in. Understand the system, incentives, and downstream impact first. Features are easy. Good decisions are not."

To help you zoom out, try asking yourself a few questions whenever you feel the urge to rush hastily into production:

- Does this solve the core problem?

- What happens if we don't build this?

- Is this a long-term solution or a temporary fix?

- How will this affect the rest of our product?

By forcing yourself to pause and answer these questions, you ensure that when you finally do move fast, you’re actually moving in the right direction.

Smart questions to ask before you start building

A short moment of reflection can prevent weeks of wasted effort. This is where you find out if your idea is actually ready for the next step. Try answering these questions as a quick gut-check:

- Why are we building this? Focus on the problem, not the feature. If your answer is “because a competitor has it,” you haven't found the core problem yet.

- Who exactly is this for? Avoid saying “all users.” Be specific, like “enterprise admins managing 500+ seats.” If the people who need this don't fit your core audience, it’s probably not a decision you need to make right now.

- How does this feature interact with existing functionality? Features don't live in a vacuum. You need to understand how this new part interacts with the functionality you already have.

- What happens after we ship this? Think about the downstream impact. Who has to support this? Will it create more work for the team later?

- What could go wrong? Edge case scenarios are important. What happens if a user skips a step or enters the wrong information?

- What does success look like? Define your metrics before you build it.

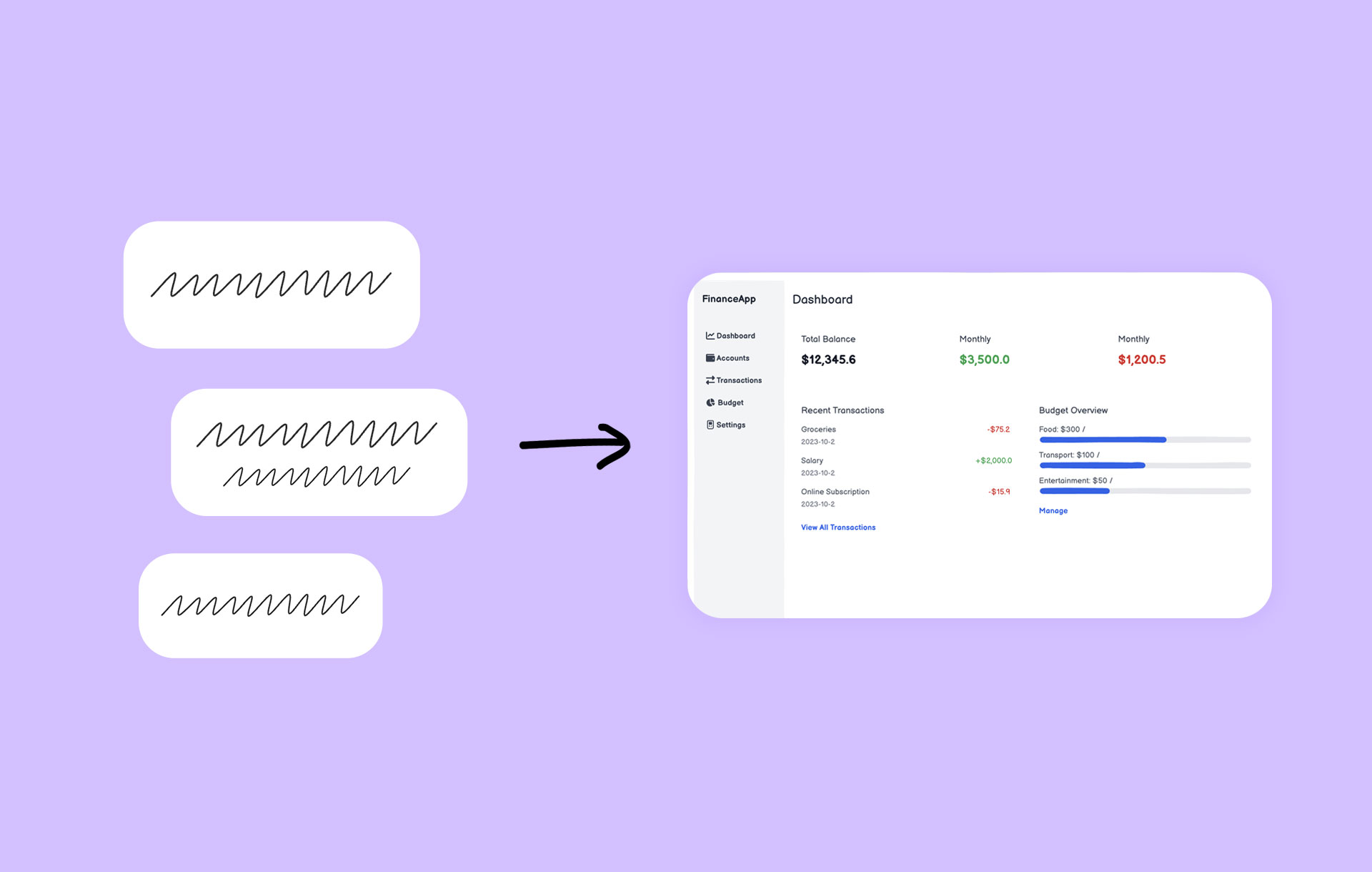

This is also where low‑fidelity thinking shines. Sketching a >quick wireframe in Balsamiq forces you to think through flows, edge cases, and logic before committing resources. It’s a simple way to test your understanding and catch gaps early.

Lesson 4: Always, always, always have a clear vision

Ambiguity is the enemy of progress. You need a clear picture of where you’re going or your team will struggle to make consistent decisions. Without a vision, you end up with a product that feels like a collection of random features that don't quite fit together. So if you don’t want to end up with a hot mess, always, always, always have a clear vision in mind.

Nick Jimenez described the PM's role in making sure the whole team shares that vision:

"Product thinking isn’t about shipping more stuff. It’s about holding a clear vision while dealing with real constraints. It can feel like a solo sport, but the real wins happen when PMs operate as a team, aligned on where the product is going and why. Most people don’t see the full picture unless the flash is on. Your job is to turn it on."

Turning the flash on means moving beyond a list of features. A solid vision means you have a firm grasp on:

- The where and the why: Not just where the product is headed, but the reason that direction matters.

- The who: A deep understanding of exactly who you’re building for and what their world looks like.

- The outcomes: Shifting the focus from “what features did we ship?” to “what did we actually achieve for the user?”

It’s also important to remember that constraints—like limited time or budget—aren't necessarily bad things. Think of them as guardrails rather than limitations. They’ll help you stay focused on the most important parts of your vision and force you to make the right decisions instead of trying to do everything all at once.

Farhan Sikder, Global Strategy and Business Advisor at BRAC IT Services LTD shared:

"In a noisy market, the best product managers are the ones who can tell the difference between a useful signal and plain noise. They know their product’s mission, vision, and the problem it aims to solve, which helps them understand who their true audience is and whose feedback matters. When the market speaks, they can sift through the clutter, identify meaningful data, and turn it into thoughtful product decisions."

How to create and maintain clarity

Vision without execution leads nowhere, but execution without vision is chaos. PMs need both to keep their team aligned and working together. There’s a few habits you can implement to make sure the vision remains front and center:

- Communicate often: Bring the big picture into daily standups and planning sessions. Don’t wait for quarterly meetings to remind people where you're going.

- Connect every “what” to a “why”: When you propose a feature, explain exactly how it supports your main goal.

- Show, don’t tell: Abstract ideas are hard to follow. Use wireframes and wireflows to turn your vision into a concrete map that everyone can understand at a glance.

When the team can see the destination, they’re less likely to get lost in the weeds.

Lesson 5: Look beyond your product

It’s easy to become obsessed with product frameworks, methodologies, and best practices. We’ve been there ourselves. You feel like if you just read one more book, listen to one more podcast, or follow one more influencer, you’ll finally have the secret to success.

But staying inside the product management bubble can actually hold you back. It creates an echo chamber where you only hear the same ideas over and over. The best product thinkers often find their best ideas in completely unrelated fields.

Simeon Superville, a Senior Product Manager at Punto Health, found that getting away from product content actually made him better at his job when he said:

"Don't get sucked down the product rabbit hole. It's so easy to go neck‑deep in frameworks, but I found this was a fast track to frustration when they couldn't be immediately applied to my work. The further away you go, the more freedom you have to think. Diversity of content equals diversity of thought."

Simply put—stepping outside the product echo chamber is a sound strategy.

What product leaders can learn from architects

For Simeon, architecture is a great place to start. It’s a field where the best work is often a response to a difficult environment.

In a video for Architectural Digest, architect Steven Harris describes building a home on the edge of an abandoned stone quarry. While most architects want a flat, easy lot, Harris saw the 40-foot cliff as an opportunity.

Instead of forcing a standard house onto the site, he used the jagged rocks and water to dictate the design. He focused on the “sequence of reveal”—how someone moves through the space and what they see at each turn.

Product managers can benefit from this mindset. When you stop worrying about “how products are supposed to work,” you can imagine entirely new approaches. Your constraints—like a tight budget or tricky tech—aren't walls; they’re the edges that define your solution. If you want to build something that feels “effortless and inevitable,” look where other PMs aren't looking.

Bonus lesson: Product thinking is built through practice

The PMs who shared their insights in this article didn't learn these lessons from textbooks. They learned them in the messy middle of real product work—from customer conversations that changed their roadmap, from saying no to their biggest client, from shipping features they wish they'd thought through longer, and from finding inspiration in places that had nothing to do with product management.

These lessons take time, but they compound. They make you a better partner to your team and a better advocate for your users. And tools like Balsamiq help along the way. Sketching early and often turns messy ideas into something teams can react to. It brings clarity faster. It helps you make better decisions before you invest in the wrong direction.

So here’s a question to consider:

What’s one thing you wish every PM knew about product thinking?

Join Good Product Club (GPC) and tell us! GPC is full of people just like you—including the PMs who shared their insights in this article. We build things, break things, and believe deeply in the value of early‑stage thinking.